Last week China's Vice Premier Li Kequiang mentioned that reforms in China have now entered "a crucial stage and cannot be delayed." And a few days earlier Prime Minister Wen Jiabao explicitly referred to the need of a second phase of growth and talked about how "political structural reform" needed to follow economic reform. In its absence "such a historic tragedy as the Cultural Revolution may happen again." These two quotes fit nicely with an article we published three years ago about how China needed to increase the pace of reforms to eventually join the club of rich economies.

The argument that institutional quality is important for growth is not new and many have written about it, but our emphasis is on the changing relationship between institutions and growth at different stages of development. In the early phases of growth the relationship between institutions and income per capita is very weak (no need for radical reform) while it becomes very strong for higher levels of development.

We just updated our original chart with more recent data (2010) and the result is shown below (institutional quality is measured as the average of the six governance indicators produced by the World Bank; GDP per capita is adjusted for PPP).

The conclusions of our previous work remain. The chart suggests that there are two phases of growth. A first one where institutional reform is less relevant. When we look at the chart we see almost no correlation between quality of institutions and income per capita for low levels of development. To be clear, not everyone is growing in that section of the chart so it must be that there is something happening in those countries that are growing (moving to the right). Success in this region is the result of good "policies" in contrast with the deep changes in institutions that are required later (you can also call them economic reforms as opposed to institutional reforms).

The second phase of growth takes countries beyond the level of $10,000-$12,000 of income per capita. It is in this second phase when the correlation between institutions and income per capita becomes strong and positive. No rich country has weak institutions so reform becomes a requirement to continue growing.

In our original article we called this region "The Great Wall". Economies either climb the wall to become rich or they hit it and get stuck. Economies that illustrate the notion of hitting the Wall are the former Soviet Union that collapsed after not being able to "go through" the Wall with its institutional setting; or Latin American economies such as Venezuela or Argentina which have incomes around that level and do not seem to be able to take their economies to the next step.

We named that threshold "The Great Wall" as a reference to China: a country that over the last decades has displayed the highest growth of income per capita in the world with a set of institutions that are seen as weak (at least relative to advanced economies). China is once again highlighted in our updated chart above and what we can see is that, while it is still in the first phase of growth, it is getting closer and closer to the Wall. It is therefore not a surprise that in the last weeks we have heard senior officials in China talking about the challenge of the next phase of growth.

Characterizing the two phases of growth and making explicit the necessary reforms that are needed to go from one to the other is not an easy task and it is likely to lead to different policy recommendations for different countries. For a very detailed analysis of institutional reform, I strongly recommend the recent book by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson Why Nations Fail. Their work highlights the need to develop inclusive institutions to allow for the second phase of growth (you can read their thoughts at their blog and find there a link to their book). Others have presented alternative views of how to think about the different phases of growth, as it is the case of Dani Rodrik, who emphasizes the role that different sectors play in this transition.

Antonio Fatás

Monday, March 26, 2012

Thursday, March 15, 2012

The missing long-term perspective on government debt.

When looking at the challenges of government debt in Europe the severity of the problem can look very different depending on the perspective one takes. If we focus on the last 5 years we see that:

1. The government of Spain has more than doubled its (net) debt measured as a % of GDP.

2. In the same period of time Italian (net) debt has also increased by about 20 percentage points of GDP.

The situation seems unmanageable and justifies a quick and radical reaction by those two governments.

But if we go back a few more years and plot the evolution of government (net) debt for these two countries in comparison to France and Germany, the message is much more comforting. [Data is Net Government Debt as % of GDP from the World Economic Outlook, IMF]

Not only the level of debt is not high by historical standards (in the case of Italy is lower than back in 1996) but it is not far from the other two European countries. Just business as usual. Spain will be slightly above Germany in the coming 5 years but still below the level of France, that has increased at a much faster pace during the last two decades.

A similar analysis can be done for other advanced economies, including the US, and one finds that the level of government debt is certainly high and has increased as a result of the crisis but it is nowhere the levels that are implied by the panic we have observed in markets and politicians when dealing with this issue.

Of course, there is an alternative and much more negative reading that one gets when looking at a longer historical perspective. Government debt is high and governments knew about it twenty years ago and they have not been able to do much about it! Yes, a crisis did not help their efforts but governments need to plan for crisis; one cannot just make budgetary plans assuming that there will never be another recession.

This reading provides a much more pessimistic assessment of fiscal policy in advanced economies. But the solution requires a long-term framework in order to deal with the inability to match spending and income in a way that keeps debt levels sustainable. We have done very little progress to address this issue and this should make us panic. But it is not the deficit in 2012 or 2013 that should worry us, they will be irrelevant in the long term. We do not need short-term austerity we need a way to deal with long-term sustainability.

Antonio Fatás

1. The government of Spain has more than doubled its (net) debt measured as a % of GDP.

2. In the same period of time Italian (net) debt has also increased by about 20 percentage points of GDP.

The situation seems unmanageable and justifies a quick and radical reaction by those two governments.

But if we go back a few more years and plot the evolution of government (net) debt for these two countries in comparison to France and Germany, the message is much more comforting. [Data is Net Government Debt as % of GDP from the World Economic Outlook, IMF]

Not only the level of debt is not high by historical standards (in the case of Italy is lower than back in 1996) but it is not far from the other two European countries. Just business as usual. Spain will be slightly above Germany in the coming 5 years but still below the level of France, that has increased at a much faster pace during the last two decades.

A similar analysis can be done for other advanced economies, including the US, and one finds that the level of government debt is certainly high and has increased as a result of the crisis but it is nowhere the levels that are implied by the panic we have observed in markets and politicians when dealing with this issue.

Of course, there is an alternative and much more negative reading that one gets when looking at a longer historical perspective. Government debt is high and governments knew about it twenty years ago and they have not been able to do much about it! Yes, a crisis did not help their efforts but governments need to plan for crisis; one cannot just make budgetary plans assuming that there will never be another recession.

This reading provides a much more pessimistic assessment of fiscal policy in advanced economies. But the solution requires a long-term framework in order to deal with the inability to match spending and income in a way that keeps debt levels sustainable. We have done very little progress to address this issue and this should make us panic. But it is not the deficit in 2012 or 2013 that should worry us, they will be irrelevant in the long term. We do not need short-term austerity we need a way to deal with long-term sustainability.

Antonio Fatás

Friday, March 2, 2012

The austerity recovery

Both Europe and the US have witnessed so far very weak recoveries from the past recession. There are many reasons why the recovery has been unusually slow: a weak real estate market, debt overhang, the fear of sovereign crisis. Some of these arguments are hard to quantify but there is one factor that is much easier to measure: the role of fiscal austerity. Although it is easy to measure, the facts seemed to have escaped the public debate for months. For a while it was common to hear the perception that government spending was constantly increasing due to successive stimulus packages approved by governments. More recently there is growing concern with the potential role of austerity in slowing down the recovery but so far it has not triggered any clear action.

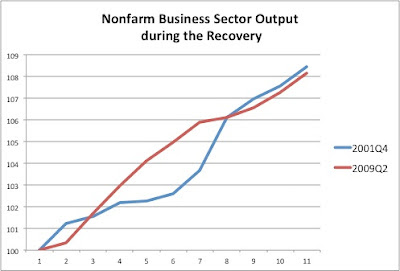

Here are three charts summarizing some key facts for the US economy. I compare below the last two recoveries: the one that started in the fourth quarter of 2001 with the one that started in the second quarter of 2009. Just to be clear, the 2001 recovery was also a slow one from a historical point of view, but it still can be an interesting benchmark. What you see below are levels relative to the quarter when the recovery started (variables are in nominal terms).

We start with GDP and we can see that 11 quarters after the recovery had started the economy was doing significantly better in the 2001 recovery than in the current one. So this recovery is even slower than the "slow" 2001 recovery.

But what if we just exclude the government sector and only measure non-farm private business sector output. The chart below shows that the two recoveries look similar from today's perspective. The 2009 recovery was stronger in the first quarters but 11 quarters after the recovery had started we are in the same position.

The analysis I am doing is clearly not complete. Each of the variables I plot are not independent. The behavior of private business output depends on government spending. How private output reacts to government spending is a source of debate as the answer depends on what economic theories you believe about the fiscal policy multiplier. But that debate cannot change the simple accounting exercise that the previous three plots do. Compared to previous US recoveries, the current one is unusual in the sense that government spending (a component of GDP) has been much weaker than in previous recoveries.

Antonio Fatás

Here are three charts summarizing some key facts for the US economy. I compare below the last two recoveries: the one that started in the fourth quarter of 2001 with the one that started in the second quarter of 2009. Just to be clear, the 2001 recovery was also a slow one from a historical point of view, but it still can be an interesting benchmark. What you see below are levels relative to the quarter when the recovery started (variables are in nominal terms).

We start with GDP and we can see that 11 quarters after the recovery had started the economy was doing significantly better in the 2001 recovery than in the current one. So this recovery is even slower than the "slow" 2001 recovery.

But what if we just exclude the government sector and only measure non-farm private business sector output. The chart below shows that the two recoveries look similar from today's perspective. The 2009 recovery was stronger in the first quarters but 11 quarters after the recovery had started we are in the same position.

And finally, what about the role of governments. I plot below government consumption and investment (which are the two components of governments that enter the GDP calculations) for the last two recoveries. Here the difference is striking. While government spending was strong during the 2001 recovery growing by about 16% in the 11 quarters that follow - faster than other components of GDP; in the 2009 recovery government spending has barely grown and has remained flat or even falling over the most recent quarters.

The analysis I am doing is clearly not complete. Each of the variables I plot are not independent. The behavior of private business output depends on government spending. How private output reacts to government spending is a source of debate as the answer depends on what economic theories you believe about the fiscal policy multiplier. But that debate cannot change the simple accounting exercise that the previous three plots do. Compared to previous US recoveries, the current one is unusual in the sense that government spending (a component of GDP) has been much weaker than in previous recoveries.

Antonio Fatás

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)